Consumer

Reports

↘

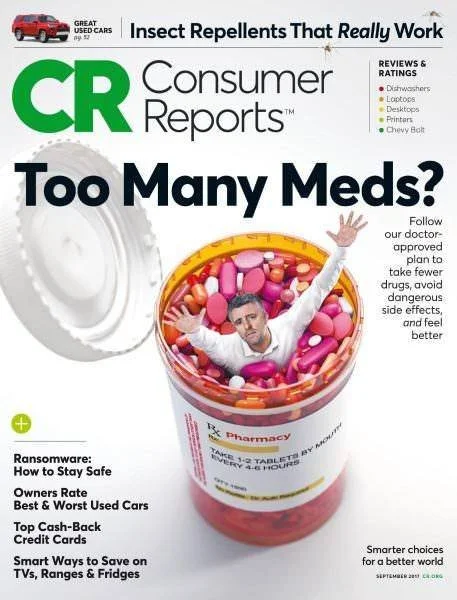

Consumer Reports, established in 1936, had the industry-best testing data but readers couldn't find it in text-heavy articles, losing ground to visual-first competitors.

Data Transformation

CONSUMER REPORTS: THE APPROACH

Strategy

Use engagement analysis to transform Consumer Reports from text-first to data-first storytelling

Solution

Make data visualization central to storytelling while building team capabilities in cross-platform design

Rollout

Built team capabilities over 18 months while unifying print and digital workflows through cross-functional collaboration

Benchmarks

Data-led content drove higher engagement while positioning Consumer Reports as the leader in transparent data presentation

CONSUMER REPORTS: VISUAL ELEMENTS

Typography

↘

Color

↘

Art Direction

↘

CONSUMER REPORTS: KEY TAKEAWAY

The Data is the Story

↘

How reader engagement revealed that data visualization should drive the narrative, not support it

AMERICA’S ROMAINE PROBLEM

Despite safety efforts, contaminated lettuce keeps making people sick—

and experts say cattle farms may be to blame

bu Kevin Loria

Photographs bu Sam Kaplan

Leafy Greens Top Food Safety Risk List

Government data shows vegetables cause more E. coli outbreaks than chicken, beef, or dairy—and contribute to other bacterial infections too

■

"These findings suggest that to solve the lettuce problem, we really have to solve the cow problem."

—Michael Hansen, Consumer Reports senior scientist

1. As Greens Grow

Toxic E. coli is found in the feces of farm animals, such as cattle and sheep. Bacteria from nearby feedlots can contaminate irrigation water or be carried by wind onto the soil or greens. The bacteria can be taken up by the plant's roots and get into the leaves.

■

"E. coli-tainted manure can run off down hills and into rivers, contaminating water sources"

■ WHEN CAROLYN GRAHAM ordered a garden salad at a pizza restaurant near her hometown of Loomis, Calif., on a weekday night in April 2018, she felt good about what she thought was a healthy choice.

But by the weekend, she had stomach cramps and diarrhea, which grew more severe with each passing hour. By 11 p.m. that Saturday, the diarrhea had turned bloody, and it continued all night long. Around 6 a.m. Sunday, she and her husband, Kenneth, headed to the emergency room. Doctors gave her fluids, oxygen, and an antibiotic, but Graham's symptoms didn't abate.

It took doctors three days of testing and analyzing results to determine that Graham had been infected with E. coli O157:H7, a dangerous strain of the bacteria that produce a substance called Shiga toxin. Graham, who was 72 and had been in excellent health, had developed a form of kidney failure called hemolytic uremic syndrome—a side effect that occurs in 5 to 10 percent of people who contract O157:H7.

Doctors put Graham on dialysis to help her kidneys function properly again, but she was going in and out of consciousness during her 14-day hospital stay. Her husband, one of her daughters, and a granddaughter stayed by her bedside until she was fully conscious and able to recognize the people around her. Then, her husband says, "she had to relearn how to talk, how to walk," a rehab process that took about two months before she was back to normal.

The culprit in Graham's ordeal? The romaine lettuce in that seemingly innocuous garden salad. That spring, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration sent out multiple national alerts, eventually telling people not to eat romaine from the Yuma, Ariz., area. Graham, it turned out, was one of 240 people across 37 states in the U.S. that spring who government officials say became sick from tainted romaine. It was the largest national E. coli O157:H7 outbreak in more than 20 years: Almost half of those affected were hospitalized, and five people from four states died. Then, right before Thanksgiving that same year, supermarkets and restaurants pulled romaine from their shelves and menus after federal officials announced yet another E. coli outbreak.

Just as consumers thought perhaps the 2018 E. coli outbreaks were a distant traumatic memory, romaine-related illnesses returned. In outbreaks starting in October 2019 and continuing into December, 133 people were sickened. This was despite steps taken over the past two years by farmers and the FDA to identify the sources of the outbreaks.

Consumer Reports is actively advocating for improved inspection and farming practices to better protect the lettuce food supply. At CR, we are also surveying Americans about their habits and working to debunk myths, including the perception that "triple washed" packaged lettuce is always safe—when, in fact, the washing process doesn't remove all harmful bacteria.

"It's astonishing how frequently the lettuce-consuming public has been exposed to bacteria like E. coli over the years," says Bill Marler, a food safety lawyer in Seattle who negotiated a settlement for Graham. "I have dozens of clients [over the years] whose lives have been completely upended," he says. "They've needed kidney transplants and had hundreds of thousands of dollars in medical expenses because they chose to eat a presumably healthy food."

In fact, between 2006 and 2019, romaine and other leafy greens, such as spinach and bags of spring mix, have been involved in at least 46 multistate E. coli outbreaks, according to the CDC. Some research shows that greens cause more cases of food poisoning than any other food, including beef.

The constant drumbeat of romaine-related E. coli outbreaks has made Americans very worried about eating lettuce. In a 2019 nationally representative Consumer Reports survey of 1,003 Americans, 52 percent admitted being concerned about getting sick from leafy greens—more than those who are worried about poisonings from beef, chicken, or eggs. Sales of romaine, which was until recently the most popular lettuce in the U.S., are down in the wake of the 2018 outbreaks, dropping about $98 million to $465 million from their $563 million peak in 2017, according to data from market research firm Nielsen. (Iceberg has regained the No. 1 spot.) Meanwhile, lettuce growers and the FDA have been trying to figure out where—from farm to fork—the potentially deadly bacteria are finding their way into and onto lettuce leaves.

Frank Yiannas, deputy commissioner for food policy and response at the FDA and the agency's top food official, told CR: "FDA has been working tirelessly to prevent these [outbreaks]. But we're going to work harder. It's a high priority for the agency and a high priority for me personally."

In the meantime, for those who want to continue to get the health benefits of leafy greens, there are safety guidelines that can help to mitigate the risk.

How did leafy greens—nutrient-packed foods recommended by doctors and nutritionists alike—become so risky? And why is romaine linked to so many of these outbreaks?

It comes down to the modern way we grow, harvest, and package our salad greens. "There are many opportunities along the continuum—from seed all the way to a consumer's plate—for greens to become contaminated," says Ben Chapman, Ph.D., a professor and food safety extension specialist at North Carolina State University in Raleigh.

Part of the reason greens in particular are so problematic is the sheer volume we're consuming. The leafy greens industry ships about 130 million servings per day all year long—enough to supply a daily salad fix to nearly 40 percent of Americans. And almost a quarter of the greens being consumed are romaine lettuce.

■ PERHAPS MOST IMPORTANT: Salad greens are almost always eaten raw, unlike burgers, eggs, flour, and many other foods that can be contaminated with pathogens but are usually cooked enough to kill any bacteria. "You can destroy E. coli and other bacteria with enough heat, but few people are going to cook their lettuce," says James E. Rogers, Ph.D., director of food safety research and testing at Consumer Reports.

"A food that doesn't have a final consumer 'kill step' presents some extra challenges [for] food safety," says Matthew Wise, Ph.D., deputy chief of the CDC's outbreak response and prevention branch. "That's probably the main driver" among a number of factors that can cause an outbreak, he says.

"We face a real dilemma with leafy greens, especially romaine lettuce," says Rogers. "They're packed with nutrients, so we don't want to discourage people from eating them. But we can't ignore the fact that leafy greens are potentially risky, perhaps one of the riskiest foods."

But, he says, we need answers on what's happening with greens sooner rather than later. "More needs to be done to determine the exact sources of contamination with dangerous bacteria," he says. "Once that's done, the FDA must set strict requirements for growers and processors, which will help prevent people from getting sick."

While the odds that you'll get sick from eating any single salad are low, Rogers says, they're real. "When you hear about 100 or 200 people contracting a foodborne illness, it may not sound like that many, but for every case of food poisoning that's reported, there are many, many more cases that never get reported." In fact, according to the CDC, for every reported case of E. coli O157:H7 infection, there are probably 26 that have gone undocumented.

Leafy greens can be the source of other bacteria that can make you sick, too. As the chart below shows, greens have been involved in outbreaks of salmonella, campylobacter, and Listeria monocytogenes in addition to E. coli.

To check for the presence of harmful bacteria, CR's food safety scientists tested 283 samples of bagged and whole heads of six types of leafy greens, including romaine, spinach, and kale, plus mixes of greens in the spring of 2019.

While we didn't find the dangerous E. coli O157:H7 implicated in recent romaine lettuce outbreaks, we did find that certain samples contained coliform bacteria. "This type of bacteria doesn't make people sick, but it's a sign that feces may have come into contact with the lettuce, and when we see it, it's considered a harbinger of possible contamination with harmful bacteria," says CR's Rogers. There was no difference in bacteria levels between whole head and packaged greens; packaged greens that were labeled "triple washed" had bacteria levels similar to those in packages marked "unwashed."

How Greens Become Contaminated

Harmful bacteria can migrate to the leaves at many points during the growing and production cycle.

2. At the Processing Plant

Greens from many fields and farms are mixed together during processing, meaning one bacteria-containing batch can contaminate many packages. Factory workers and unsanitized equipment present additional threats during processing.

3. When They’re Harvested

Farming equipment and workers' hands can transfer bacteria to greens during harvest. Cutting the greens creates entry points for bacteria and releases nutrients that support bacterial growth.

Once the greens grow to maturity, they're harvested, mostly by hand, Boelts says. Growers take samples of the greens to check for harmful bacteria (but they don't check every leaf, which is why the bacteria sometimes slip through). Some greens are packed right in the field, to be immediately cooled and shipped to stores. Greens that are destined to be bagged or sold in plastic containers—65 percent of Americans buy packaged greens, according to market research firm Mintel—are taken from the field to processing plants, where tons of lettuce from multiple farms are mixed together. (Romaine is produced to the tune of 1.5 million tons per year.) There, the lettuce is usually washed in water that contains chlorine or another sanitizer, then rinsed, dried, packaged, and shipped to supermarkets and restaurants across the country.

What any lettuce farmer will tell you is that he or she fears the animals that live around lettuce fields. That's because E. coli O157:H7 and other strains of illness-causing bacteria live in the guts of cattle and other animals, including sheep, deer, wild boar, and even birds. Although the E. coli bacteria don't usually make the animals sick, when they defecate they deposit dangerous bacteria into the soil and water around them. That contaminated soil could later end up mixed with dirt tracked by equipment, people, or animals onto a field full of leafy greens, or rain could wash the bacteria into one of the open irrigation canals that are so important for lettuce-growing regions.

This route to food poisoning has been known about for longer than a decade: In 2006, in an E. coli O157:H7 outbreak linked to spinach, federal officials said that a possible source was waste from feral pigs that got into growing fields.

Because animals can contaminate their valuable crops, farmers put a lot of effort into keeping them away. "We pay people to stand by fields and scare birds off," Boelts says. "We surround fields with 8-foot-tall fences, prohibiting animals from being on our farm. We're doing everything science says we should," he says.

But contamination still occurs, and experts and research say it's because fields of leafy greens are sometimes located next door to large cattle farms known as concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs).

"It's because of the proximity of cattle feedlots to fresh produce fields," says Keith Warriner, Ph.D., a professor in the department of food science at the University of Guelph in Ontario who has studied foodborne illness linked to produce. "In the Salinas Valley, you'll see cattle roaming the hills." (Romaine from the Salinas region was linked to the outbreaks in fall 2018 and fall 2019.) "With every outbreak, there's a cow somewhere," says attorney Marler, who has tracked food-poisoning incidents linked to greens for almost 20 years.

It has also been suspected that bacteria mix with the soil and become part of the dust, which can be carried by the wind from a CAFO and deposited onto the greens as they grow in the field. But experts and investigators from the FDA and CDC have focused on contaminated irrigation water as the most likely vector. "E. coli-tainted manure can run off down hills and into rivers, contaminating water sources," Warriner says.

CONSUMER REPORTS: DESKTOP DESIGN

CONSUMER REPORTS: CR MAGAZINE

Index